- Stephen Theaker reviews Tarun K. Saint’s anthology The Gollancz Book of South Asian Speculative Fiction, available in the UK from 3 June as New Horizons. (4 February).

- Indrapramit Das interviewed about his writing process in The Hindustan Times. (4 June)

- A roundtable discussion on Indian Science Fiction with Suparno Banerjee, Sumit Bardhan, Sandipan Ganguly and Dip Ghosh, at Facebook’s Asian Science Fiction & Fantasy group. (6 June)

- Lavie Tidhar on The Unsung History of Jewish Writers and the Birth of Science Fiction, at LitHub. (14 June)

- Ng Yi-Sheng summarises Dean Francis Alfar’s talk Asian Speculative Fiction 101, at Facebook. (25 June)

- Trailer for Marvel Studios’ Chinese superhero movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, in cinemas from September. (25 June)

Tag: Reviews

ICYMI: Links round-up, April 2021

- Hillary Kelly butts up against Haruki Murakami’s latest collection First Person Singular, reviewed in the Los Angeles Times. (1 April) … Rob Doyle at The Guardian is a little kinder, but not by much. (12 April)

- A 1-hour podcast from Kuzhali Manickavel on writing English in India, plus a short story she discusses, ‘Item Girls’, at Granta Online. (2 April)

- Aamer Hussain on Usman T. Malik: The Fabulist of Lahore at Dawn. (4 April)

- Singaporean spec-fic authors Suffian Hakim and Jocelyn Suarez discuss telling dark stories at Singapore Time Out. (5 April)

- Emad El-Din Aysha interviews Malaysian writer Chuah Gaut Eng about her only science fiction story ‘Memoirs of an Aranaean Harpist’ at Eksentrika.com. (22 April)

- Lee Mandelo at Tor.com reviews Terminal Boredom, the first of two collections from the iconic Japanese writer Izumi Suzuki. (22 April)

- Asian SEA Story on Facebook has an overview of 10 ghosts and ghouls from across Southeast Asia. (25 April)

ICYMI: Links round-up, January–March 2021

- Desirée Custers on Arab and African Science Fiction: (re)claiming the past, reflecting on the present, and envisioning the future. (26 February)

- Ziya Jones interviews Zeyn Joukhadar about her new novel The Thirty Names of Night: “It’s Powerful to Let People Love You with a Name that You Chose for Yourself”, at Hazlitt. (2 March)

- Okuma Yuichiro interviews Liu Cixin on Humanity, Crisis, and Changes at Chinese Literature Today. (5 March)

- Aliette de Bodard at LocusMag: excerpt from the interview ‘Where Is It Written?’ (15 March)

- Ng Yi-Sheng at Facebook on Zen Cho’s 2020 novella The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water ... some useful commentary. (21 March)

- Emad El-Din Aysha interviews Dr. Csicsery-Ronay Istvan on The Golden Mean Between Local and Global SF, at The Levant News. (25 March)

- Marc de Faoite’s review of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun at The Vibes.com. (27 March 2021)

- Jaideep Unudurti reviews the latest tome from J. Furcifer Bhairav and Rakesh Khanna, Blaft Publications’ encyclopedic Ghosts, Monsters, and Demons of India at Open Magazine. (26 March)

- The latest Strange Horizons issue is a Palestinian Special. (29 March)

Reviews: 3 x Kaiju

James Morrow, Shambling Towards Hiroshima, 2009

TACHYON PUBLICATIONS, 2009, ISBN 978-1-892391-84-1, trade paperback, $14.95

In 1945 the US Navy developed a top secret biological weapon: giant mutant fire-breathing iguanas bred to stomp Japanese cities. Hollywood monster-suit actor Syms Thorley is drafted to put terror into the hearts of a group of visiting Japanese diplomats with his depiction of what might happen if Emperor Hirohito doesn’t surrender; and if that doesn’t work there’s always the Manhattan Project. Shambling Towards Hiroshima takes the form of a suicide note written at a 1984 horror movie convention in Baltimore, but outside of that frame this is a lovingly crafted satire that is also a tribute to Hollywood’s monster movies, with educated nods in all directions. The first three quarters of this novella feels self-consciously ridiculous because Morrow is depicting military life imitating what is essentially a pretty ridiculous art, but he has serious points to make and there comes a well crafted moment towards the end at which he wants you stop laughing and consider a few things. Morrow is interviewed on video about the story here, but I’m glad I indulged in this wry, clever book first.

Hiroshi Yamamoto, MM9, 2007

Translated by Nathan Collins

HAIKASORU, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4215-4089-4, trade paperback, $14.99

What if the world had a Richter-like scale for monster attacks? And where better to show how the whole thing works than in Japan? Given that this is such a brilliant idea, when teamed up with this book’s self-serving ending it was probably inevitable that a TV series would result from this fix-up of episodic short stories about the Monsterological Measures Department, doing battle to contain outbreaks of kaiju activity across Japan. As a science fiction writer, Yamamoto’s first priority had to be that of getting around the law of conservation of mass to account for the extraordinary size of some monsters and their unlikely ability to support themselves/breathe fire/stomp buildings with apparent ease, and Yamamoto has given his monsters a clever yet almost whimsical explanation that conveniently excuses them from the laws of physics of our universe. Yamamoto’s speculation in this aspect of the novel is engaging but not always rigourous, and when evaluated by his characters the explanations are often too easily accepted by the MMD without a great deal of debate because, well, there’s a monster to defeat now and it answers the problem of how to tackle the kaiju somehow. I admit to approaching MM9 from the wrong direction at first, expecting a more tongue-in-cheek and self-knowing escapade than the straightforward episodic adventure we were given, but after realising how I should be reading it this novel was good fun, and Yamamoto’s mythical monsters are always neat inventions. I’m now awaiting a dubbed/subtitled DVD release of the TV series with bated breath.

Reviews: Short fiction chapbooks – 2 from Japan, 1 from China

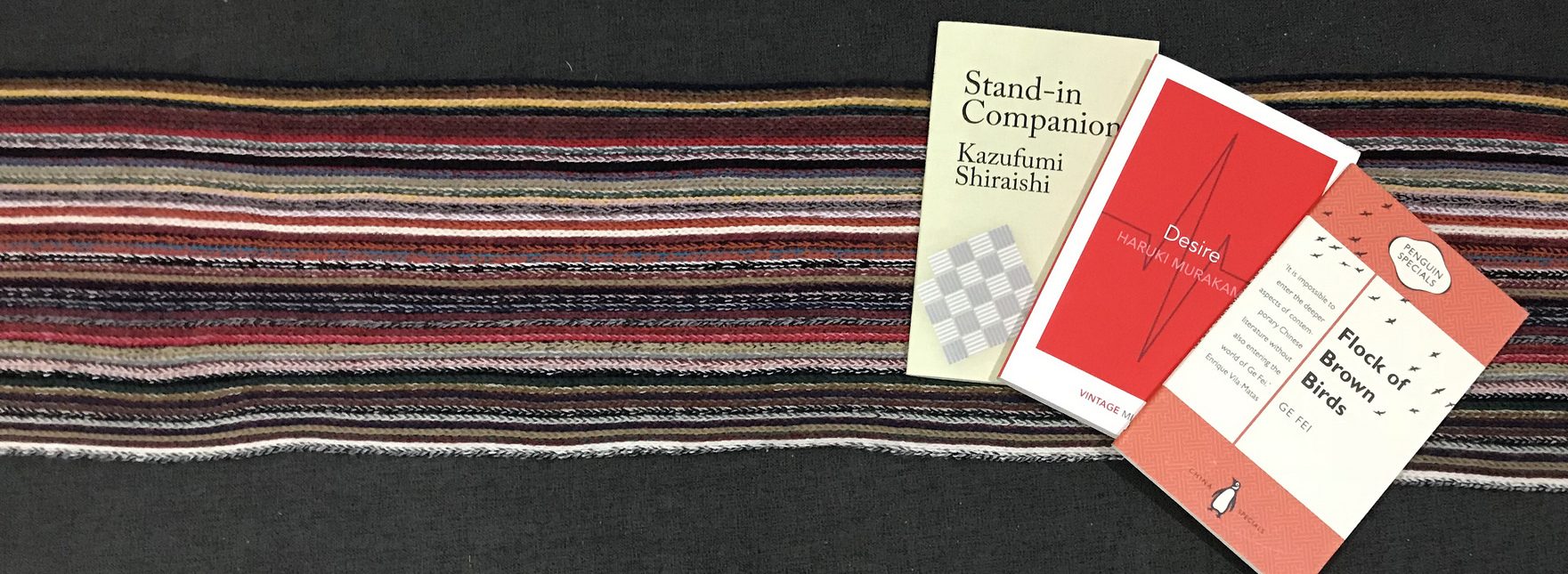

Kazufumi Shiraishi, ‘Stand-in Companion’, 2018

Translated by Raj Mahtani

RED CIRCLE, 2018, ISBN 978-1-912864-00-3, paperback, £7.50

xxx

Haruki Murakami, Desire, 2017

Translated by Jay Rubin, Ted Goossen and Philip Gabriel

VINTAGE, 2017, ISBN 978-1-78487-263-2, paperback, £3.50

There are two genre stories in this small collection, one being ‘Birthday Girl’, but more interesting to Kafka readers like myself is ‘Samsa in Love’. Here we have a cockroach that wakes up one morning to discover he is a human named Gregor Samsa, protagonist of Franz Kafka’s most famous story ‘Metamorphosis’. Murakami takes full advantage of this premise but the reader really needs to be familiar with Kafka’s story (which can be found just about everywhere); he unfolds the story as much for insight as for laughs, especially when he experiences his new body’s reactions when encountering a female human who might not be considered ‘attractive’ in the conventional sense.

Ge Fei, ‘Flock of Brown Birds’, 1989

Translated by Poppy Toland

PENGUIN, 2015, ISBN 978-0-7343-9960-1, paperback, $9.95

Ge himself declares about this story in the Author’s Preface, “Whenever anyone complained to me about how difficult it was to understand, I would give the joking response, ‘I don’t blame you. I’m not sure I understand it either.’” This Preface, written thirty years after the story itself, gives context to how revolutionary the story was to Chinese literature when it first appeared, and Ge acknowledges the avant-garde, experimental nature of the writing. It concerns a writer named Ge Fei, who has seemingly poor memory and who has retreated to the Chinese countryside to complete a novel. He is visited by an unknown woman who prompts him to tell the mysterious story of his late wife. The story feels like a dance around the memory of a dream, recapturing certain scenes while improvising others that have less faithful recall, and it binds together in playful fashion the temporal disorientation that is always inherent in stories of circular time and a loosely-grasped reality. Perhaps that makes the sense that Ge is searching for or perhaps it doesn’t; either way, to get an angle on experimental Chinese ‘pioneer’ literature of that era this is a must-read.

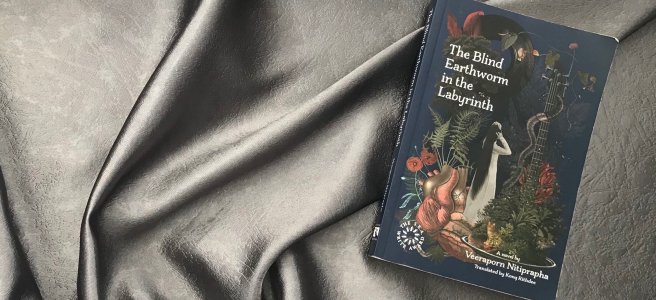

Review: Veeraporn Nitiprapha, The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth, 2015

While on the closing chapters of this mostly mainstream novel I decided this was one of my favourite books of 2018, the superb 2015 SEA Write Award winner now translated into English. It’s the story of three grown-up orphans, two sisters and a male musician, making their way in 1980s/90s Bangkok as they try to escape their fates, with frequent digressions into music, food, sex and the occasional, inevitable supernatural encounter. The whole experience reads a bit like a ‘lakorn’ (a Thai TV soap opera) but with much more depth and characters you feel for; the ramshackle townhouse they live in, replete with birds and a great variety of flora, is also depicted especially well.

But it’s the three central characters who enchant the most, the two sisters Chareeya and Chalika who mostly try to avoid drama, Pran the taciturn boy who plays bass in a Bangkok band and has differing but complex relationships with both girls. Also of particular interest among the cast of secondary characters is Uncle Thanit, a travelling cloth merchant who takes care of them from afar and who finally disappears into another world in Xinghai, China – this episode alone would make a great short story if it was slightly rewritten and independently published.

The book may have an oddly gothic title and beautiful cover art, but I didn’t want The Blind Earthworm in the Labyrinth to end simply because Kuhn Veeraporn writes so well. The complexities of translating all this richness into sophisticated English must be recognised too, and this deserves to be far more widely read beyond the borders of Thailand.

WINNER OF THE S.E.A. WRITE AWARD 2015

TRANSLATED BY KONG RITHDEE

~ MOST RECENT EDITION ~

Thailand: River Books, 2018, ISBN 978-616-451-013-5, Trade Paperback, 207 pages, ฿399

Review: Chan Koonchung, The Fat Years, 2009

This novel has one of the best introductions I’ve come across in a long while: an essay by the sinologist Julia Lovell, in which she both places the novel in its present-day sociological context and also sets the stage admirably for the story to come: in a near-future China a month has gone missing, not only from official records but also from peoples’ memories, and no one could care less. But there’s also a group of unaffected people who collectively try to find out the reason for this cheerful cultural amnesia about certain events the Party wishes to ‘erase’, and something radical has to be done to discover what mark China plans to make on the rest of the world. The Fat Years is only a dystopia on its thin surface – China emerged from something far worse in real life from the Great Leap Forward to the Cultural Revolution; today there’s no Mao-like figure, the Party is driven more by pragmatism than ideology and has an unspoken contract with the people: “tolerate our authoritarianism, and we will make you rich”. Explored admirably here, the bigger question then becomes, “Between a good hell and a fake paradise, which one would you choose?”, so ‘post-dystopia’ would definitely be a more accurate description. China also has leaders with a variety of agendas ranging from outright fascism to the spread of democracy and Christianity, and these disparate groups are all characterised in the novel. Yes, there are Orwellian undertones, but they only underpin this exploration of China’s very likely future, with good characterisation and a little too much info-dumping. Still, this is a necessary and challenging book.