- Hillary Kelly butts up against Haruki Murakami’s latest collection First Person Singular, reviewed in the Los Angeles Times. (1 April) … Rob Doyle at The Guardian is a little kinder, but not by much. (12 April)

- A 1-hour podcast from Kuzhali Manickavel on writing English in India, plus a short story she discusses, ‘Item Girls’, at Granta Online. (2 April)

- Aamer Hussain on Usman T. Malik: The Fabulist of Lahore at Dawn. (4 April)

- Singaporean spec-fic authors Suffian Hakim and Jocelyn Suarez discuss telling dark stories at Singapore Time Out. (5 April)

- Emad El-Din Aysha interviews Malaysian writer Chuah Gaut Eng about her only science fiction story ‘Memoirs of an Aranaean Harpist’ at Eksentrika.com. (22 April)

- Lee Mandelo at Tor.com reviews Terminal Boredom, the first of two collections from the iconic Japanese writer Izumi Suzuki. (22 April)

- Asian SEA Story on Facebook has an overview of 10 ghosts and ghouls from across Southeast Asia. (25 April)

Category: Japan

Adorable!

Minimum 45 degrees means they really are spectacularly sorry!

Reviews: 3 x Kaiju

James Morrow, Shambling Towards Hiroshima, 2009

TACHYON PUBLICATIONS, 2009, ISBN 978-1-892391-84-1, trade paperback, $14.95

In 1945 the US Navy developed a top secret biological weapon: giant mutant fire-breathing iguanas bred to stomp Japanese cities. Hollywood monster-suit actor Syms Thorley is drafted to put terror into the hearts of a group of visiting Japanese diplomats with his depiction of what might happen if Emperor Hirohito doesn’t surrender; and if that doesn’t work there’s always the Manhattan Project. Shambling Towards Hiroshima takes the form of a suicide note written at a 1984 horror movie convention in Baltimore, but outside of that frame this is a lovingly crafted satire that is also a tribute to Hollywood’s monster movies, with educated nods in all directions. The first three quarters of this novella feels self-consciously ridiculous because Morrow is depicting military life imitating what is essentially a pretty ridiculous art, but he has serious points to make and there comes a well crafted moment towards the end at which he wants you stop laughing and consider a few things. Morrow is interviewed on video about the story here, but I’m glad I indulged in this wry, clever book first.

Hiroshi Yamamoto, MM9, 2007

Translated by Nathan Collins

HAIKASORU, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4215-4089-4, trade paperback, $14.99

What if the world had a Richter-like scale for monster attacks? And where better to show how the whole thing works than in Japan? Given that this is such a brilliant idea, when teamed up with this book’s self-serving ending it was probably inevitable that a TV series would result from this fix-up of episodic short stories about the Monsterological Measures Department, doing battle to contain outbreaks of kaiju activity across Japan. As a science fiction writer, Yamamoto’s first priority had to be that of getting around the law of conservation of mass to account for the extraordinary size of some monsters and their unlikely ability to support themselves/breathe fire/stomp buildings with apparent ease, and Yamamoto has given his monsters a clever yet almost whimsical explanation that conveniently excuses them from the laws of physics of our universe. Yamamoto’s speculation in this aspect of the novel is engaging but not always rigourous, and when evaluated by his characters the explanations are often too easily accepted by the MMD without a great deal of debate because, well, there’s a monster to defeat now and it answers the problem of how to tackle the kaiju somehow. I admit to approaching MM9 from the wrong direction at first, expecting a more tongue-in-cheek and self-knowing escapade than the straightforward episodic adventure we were given, but after realising how I should be reading it this novel was good fun, and Yamamoto’s mythical monsters are always neat inventions. I’m now awaiting a dubbed/subtitled DVD release of the TV series with bated breath.

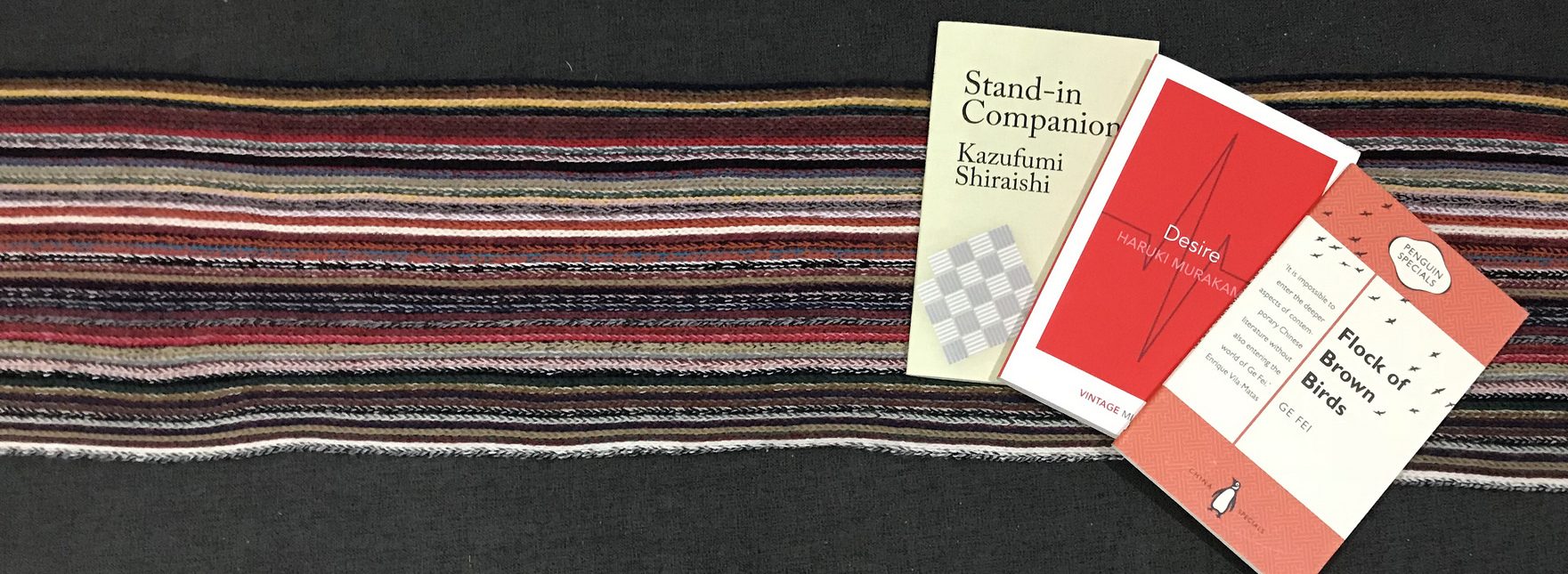

Reviews: Short fiction chapbooks – 2 from Japan, 1 from China

Kazufumi Shiraishi, ‘Stand-in Companion’, 2018

Translated by Raj Mahtani

RED CIRCLE, 2018, ISBN 978-1-912864-00-3, paperback, £7.50

xxx

Haruki Murakami, Desire, 2017

Translated by Jay Rubin, Ted Goossen and Philip Gabriel

VINTAGE, 2017, ISBN 978-1-78487-263-2, paperback, £3.50

There are two genre stories in this small collection, one being ‘Birthday Girl’, but more interesting to Kafka readers like myself is ‘Samsa in Love’. Here we have a cockroach that wakes up one morning to discover he is a human named Gregor Samsa, protagonist of Franz Kafka’s most famous story ‘Metamorphosis’. Murakami takes full advantage of this premise but the reader really needs to be familiar with Kafka’s story (which can be found just about everywhere); he unfolds the story as much for insight as for laughs, especially when he experiences his new body’s reactions when encountering a female human who might not be considered ‘attractive’ in the conventional sense.

Ge Fei, ‘Flock of Brown Birds’, 1989

Translated by Poppy Toland

PENGUIN, 2015, ISBN 978-0-7343-9960-1, paperback, $9.95

Ge himself declares about this story in the Author’s Preface, “Whenever anyone complained to me about how difficult it was to understand, I would give the joking response, ‘I don’t blame you. I’m not sure I understand it either.’” This Preface, written thirty years after the story itself, gives context to how revolutionary the story was to Chinese literature when it first appeared, and Ge acknowledges the avant-garde, experimental nature of the writing. It concerns a writer named Ge Fei, who has seemingly poor memory and who has retreated to the Chinese countryside to complete a novel. He is visited by an unknown woman who prompts him to tell the mysterious story of his late wife. The story feels like a dance around the memory of a dream, recapturing certain scenes while improvising others that have less faithful recall, and it binds together in playful fashion the temporal disorientation that is always inherent in stories of circular time and a loosely-grasped reality. Perhaps that makes the sense that Ge is searching for or perhaps it doesn’t; either way, to get an angle on experimental Chinese ‘pioneer’ literature of that era this is a must-read.