- Kazuo Ishiguro goes into the history of his novel Never Let Me Go and compares it to his latest novel Klara and the Sun, at Goodreads. (1 May)

- E. Lily Yu’s personal ‘A Love Letter to Libraries’ at Uncanny Magazine. (4 May)

- Gary K. Wolfe reviews E. Lily Yu’s first non-genre novel On Fragile Waves and assesses the minimal fantasy therein, at Locus. (10 May)

- “Is there such a thing as Indian science fiction?” Sumit Bardhan assesses Suparno Banerjee’s Indian Science Fiction: Patterns, History and Hybridity, at Scroll.in. (16 May)

- Sean Wilsey in conversation with Haruki Murakami, at InsideHook. (25 May)

- Kerry Dodd reviews the Strugatsky Brothers’ The Doomed City, at the BSFA Review. (29 May)

Category: Haruki Murakami

ICYMI: Links round-up, April 2021

- Hillary Kelly butts up against Haruki Murakami’s latest collection First Person Singular, reviewed in the Los Angeles Times. (1 April) … Rob Doyle at The Guardian is a little kinder, but not by much. (12 April)

- A 1-hour podcast from Kuzhali Manickavel on writing English in India, plus a short story she discusses, ‘Item Girls’, at Granta Online. (2 April)

- Aamer Hussain on Usman T. Malik: The Fabulist of Lahore at Dawn. (4 April)

- Singaporean spec-fic authors Suffian Hakim and Jocelyn Suarez discuss telling dark stories at Singapore Time Out. (5 April)

- Emad El-Din Aysha interviews Malaysian writer Chuah Gaut Eng about her only science fiction story ‘Memoirs of an Aranaean Harpist’ at Eksentrika.com. (22 April)

- Lee Mandelo at Tor.com reviews Terminal Boredom, the first of two collections from the iconic Japanese writer Izumi Suzuki. (22 April)

- Asian SEA Story on Facebook has an overview of 10 ghosts and ghouls from across Southeast Asia. (25 April)

Reviews: Short fiction chapbooks – 2 from Japan, 1 from China

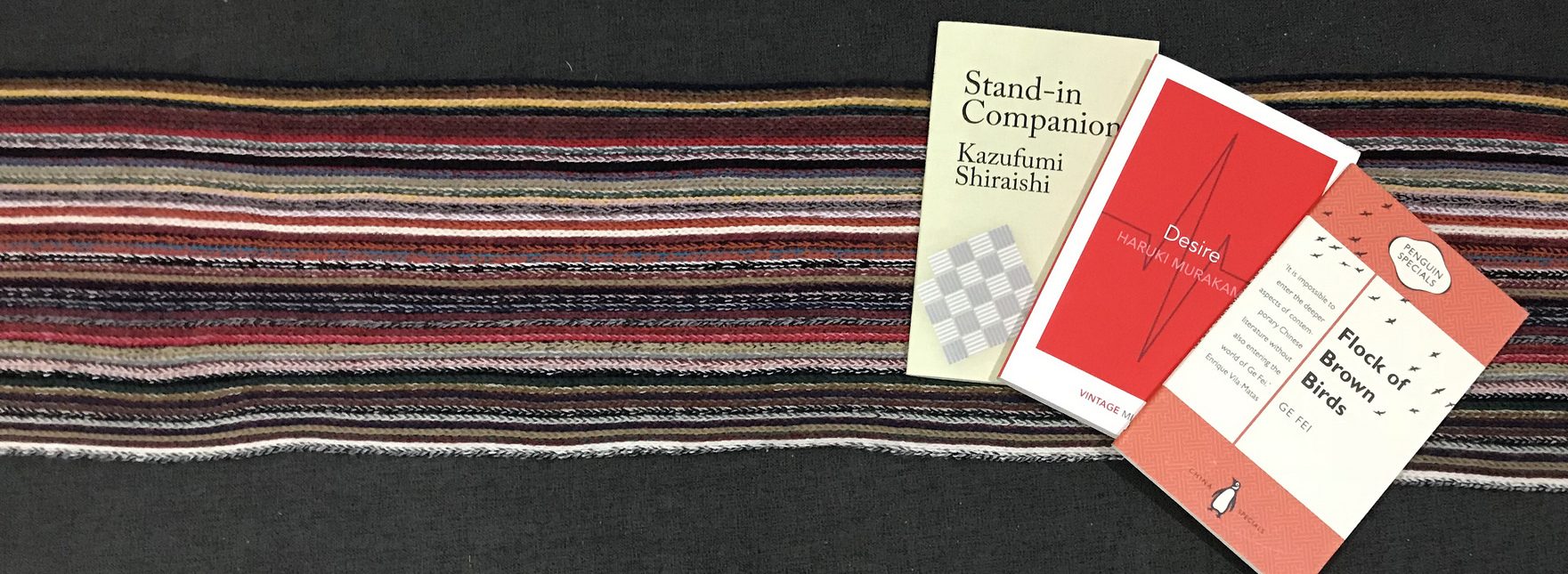

Kazufumi Shiraishi, ‘Stand-in Companion’, 2018

Translated by Raj Mahtani

RED CIRCLE, 2018, ISBN 978-1-912864-00-3, paperback, £7.50

xxx

Haruki Murakami, Desire, 2017

Translated by Jay Rubin, Ted Goossen and Philip Gabriel

VINTAGE, 2017, ISBN 978-1-78487-263-2, paperback, £3.50

There are two genre stories in this small collection, one being ‘Birthday Girl’, but more interesting to Kafka readers like myself is ‘Samsa in Love’. Here we have a cockroach that wakes up one morning to discover he is a human named Gregor Samsa, protagonist of Franz Kafka’s most famous story ‘Metamorphosis’. Murakami takes full advantage of this premise but the reader really needs to be familiar with Kafka’s story (which can be found just about everywhere); he unfolds the story as much for insight as for laughs, especially when he experiences his new body’s reactions when encountering a female human who might not be considered ‘attractive’ in the conventional sense.

Ge Fei, ‘Flock of Brown Birds’, 1989

Translated by Poppy Toland

PENGUIN, 2015, ISBN 978-0-7343-9960-1, paperback, $9.95

Ge himself declares about this story in the Author’s Preface, “Whenever anyone complained to me about how difficult it was to understand, I would give the joking response, ‘I don’t blame you. I’m not sure I understand it either.’” This Preface, written thirty years after the story itself, gives context to how revolutionary the story was to Chinese literature when it first appeared, and Ge acknowledges the avant-garde, experimental nature of the writing. It concerns a writer named Ge Fei, who has seemingly poor memory and who has retreated to the Chinese countryside to complete a novel. He is visited by an unknown woman who prompts him to tell the mysterious story of his late wife. The story feels like a dance around the memory of a dream, recapturing certain scenes while improvising others that have less faithful recall, and it binds together in playful fashion the temporal disorientation that is always inherent in stories of circular time and a loosely-grasped reality. Perhaps that makes the sense that Ge is searching for or perhaps it doesn’t; either way, to get an angle on experimental Chinese ‘pioneer’ literature of that era this is a must-read.